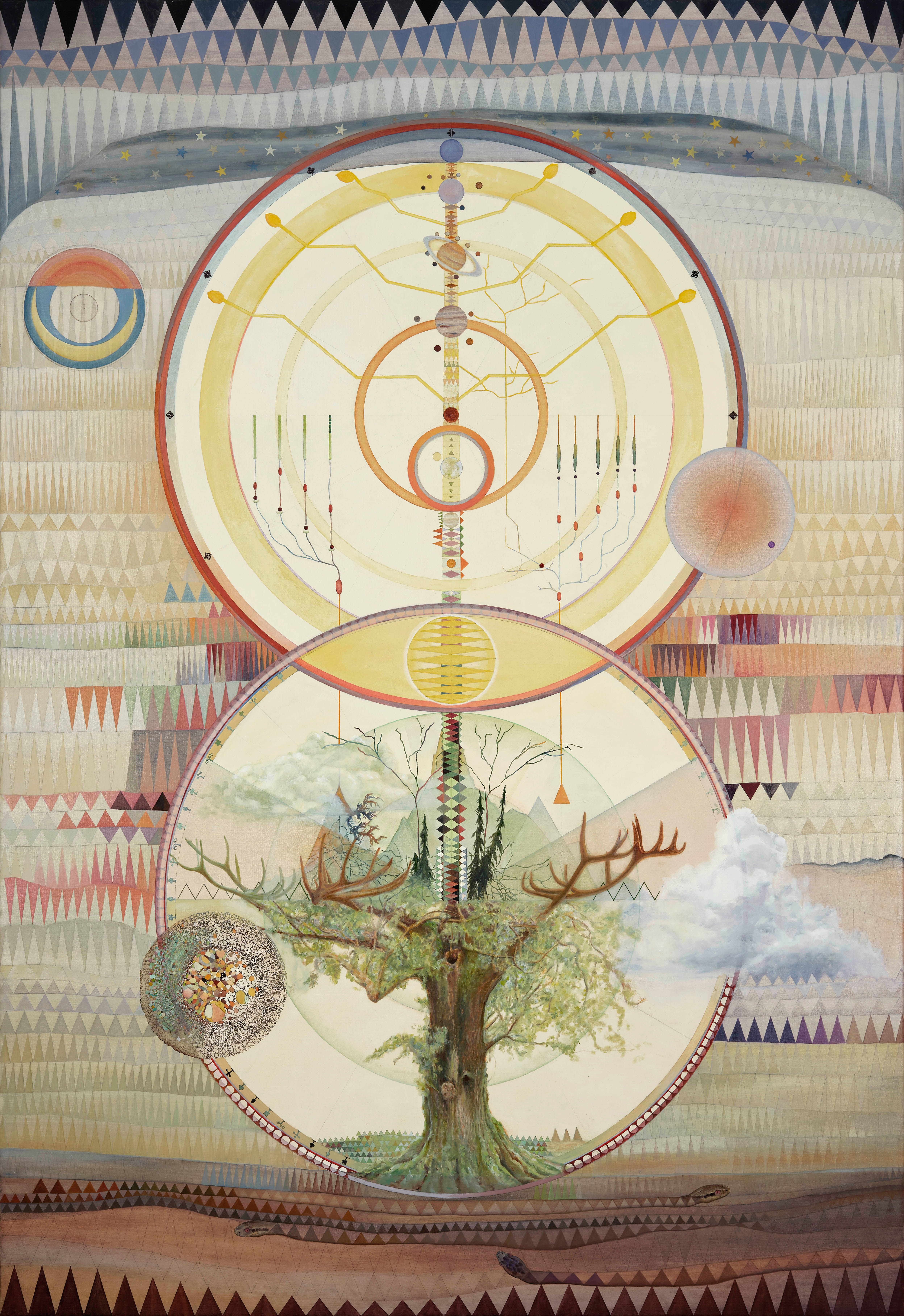

Christine Ödlund

Världsträdet / The World Tree

, 2024The tree of life (a fundamental archetype in many of the world’s mythological, religious and philosophical traditions) is closely related to the concept of the sacred tree. The tree connecting to heaven as well as the underworld (like the Norse Yggdrasil), the tree of the knowledge of good and evil in Genesis and the tree of life (connecting all forms of creation) are merely different versions of the world tree, or cosmic tree, often portrayed in various religions and philosophies as the same tree.

The Assyrian tree of life was represented by a series of nodes and crisscrossing lines. It was apparently an important religious symbol, often attended to in Assyrian palace reliefs by human or eagle-headed winged genies. A genre of the sacred books of hinduism, the Puranas, mention a divine tree called the Kalpavriksha. This divine tree is guarded by gandharvas in the garden of the mythological city of Amaravati under the control of Indra, the king of the devas. In Chinese mythology, a carving of a tree of life depicts a phoenix and a dragon (the dragon often representing immortality) with a Taoist story telling of a tree that produces a peach every three thousand years, and anyone who eats the fruit receives immortality.

In Greek mythology, Hera is gifted (by her grandmother Gaia) a branch growing golden apples which is then planted in Hera’s Garden of the Hesperides. The dragon Ladon guards the tree(s) from all who would take the apples. The three golden apples that Aphrodite gave to Hippomenes, to distract Atalanta three times during their footrace, allowed him to win Atalanta’s hand in marriage. Though it is not specified in ancient myth, many assume that Aphrodite gathered those apples from Hera’s tree (Eris stole one of these apples and carved the words ΤΗΙ ΚΑΛΛΙΣΤΗΙ, ‘to the fairest’, upon it to create the Apple of Discord). Heracles also, famously, retrieved three of the apples as the eleventh of his Twelve Labors. The Garden of the Hesperides is often compared to Eden whilst the golden apples are compared to the forbidden fruit of the tree in Genesis (Ladon is also often compared to the snake in Eden), all of which is part of why the forbidden fruit of Eden is usually represented as an apple in European art, even though Genesis does not specifically name nor describe any characteristics of the fruit.

In Germanic paganism, trees played (and, in the form of reconstructive Heathenry and Germanic Neopaganism, continue to play) a prominent role, appearing in various aspects of surviving texts and possibly in the name of gods. The tree of life appears in Norse religion as Yggdrasil, the world tree, a massive tree (sometimes considered a yew or ash tree) with extensive lore surrounding it. Perhaps related to Yggdrasil, accounts have survived of Germanic Tribes honouring sacred trees within their societies. Examples include Thor’s Oak, sacred groves, the Sacred tree at Uppsala, Sweden and the wooden Irminsul pillar. In Norse Mythology, the apples from Iðunn’s ash box provide immortality for the gods.

Etz Chaim (עץ חיים), Hebrew for ‘tree of life,’ is a common term used in Judaism. The expression, found in the Book of Proverbs, is figuratively applied to the Torah itself. Etz Chaim is also a common name for yeshivas and synagogues as well as for works of Rabbinic literature. It is also used to describe each of the wooden poles to which the parchment of a Sefer Torah is attached. The tree of life is mentioned in the Book of Genesis; it is distinct from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. After Adam and Eve disobeyed God by eating fruit from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, they were driven out of the Garden of Eden. Remaining in the garden, however, was the tree of life. To prevent their access to this tree in the future, Cherubim with a flaming sword were placed at the east of the garden. In the Book of Proverbs, the tree of life is associated with wisdom: ‘[Wisdom] is a tree of life to them that lay hold upon her, and happy [is every one] that retaineth her.’ In Proverbs 15:4, the tree of life is associated with calmness: ‘A soothing tongue is a tree of life; but perverseness therein is a wound to the spirit.’ Jewish mysticism depicts the tree of life in the form of ten interconnected nodes, as the central symbol of the Kabbalah. It comprises the ten Sefirot powers in the divine realm. The panentheistic and anthropomorphic emphasis of this emanationist theology interpreted the Torah, Jewish observance, and the purpose of Creation as the symbolic esoteric drama of unification in the sefirot, restoring harmony to Creation. From the Renaissance onwards, Kabbalah became incorporated as tradition in Christian Western esotericism as Hermetic Qabalah.

The tree of life first appears in Genesis 2:9 and 3:22–24 as the source of eternal life in the Garden of Eden, from which access is revoked when man is driven from the garden. It then reappears in the last book of the Bible, the Book of Revelation, and most predominantly in the last chapter of that book (Chapter 22) as a part of the new garden of paradise. Access is then no longer forbidden, for those who ‘wash their robes’ (or as the textual variant in the King James Version has it, ‘they that do his commandments’) ‘have right to the tree of life’ (v. 14). A similar statement appears in Rev 2:7, where the tree of life is promised as a reward to those who overcome. Revelation 22 begins with a reference to the ‘pure river of water of life’ which proceeds ‘out of the throne of God’. The river seems to feed two trees of life, one ‘on either side of the river’ which ‘bear twelve manner of fruits’ ‘and the leaves of the tree were for healing of the nations’ (v. 1–2). Alternatively, this may indicate that the tree of life is a vine that grows on both sides of the river, as John 15:1 would hint at.

The ‘Tree of Immortality’ (شجرة الخلود) is the tree of life motif as it appears in the Quran. It is also alluded to in hadiths and tafsir. Unlike the biblical account, the Quran mentions only one tree in Eden, also called ‘the tree of immortality and power that never decays’, which God specifically forbade to Adam and Eve. The tree in Quran is used as an example of a concept, idea, way of life or code of life. A good concept/idea is represented as a good tree and a bad idea/concept is represented as a bad tree. Muslims believe that when God created Adam and Eve, he told them that they could enjoy everything in the Garden except this tree (idea, concept, way of life). Satan appeared to them and told them that the only reason God forbade them to eat from that tree was that they would become angels or they start using the idea/concept of Ownership in conjunction with inheritance generations after generations which Iblis convinced Adam to accept. When Adam and Eve ate from this tree their nakedness appeared to them and they began to sew together, for their covering, leaves from the Garden.

The tree of life in Islamic architecture is a type of biomorphic pattern found in many artistic traditions. It is considered to be any vegetal pattern with a clear origin or growth. The pattern in al-Azhar Mosque, Cairo’s mihrab, a unique Fatimid architectural variation, is a series of two or three leave palmettes with a central palmette of five leaves from which the pattern originates. The growth is upwards and outwards and culminates in a lantern like flower towards the top of the niche above which is a small roundel. The curvature of the niche accentuates the undulating movement which despite its complexity is symmetrical along its vertical axis. The representations of varying palm leaves hints to spiritual growth attained through prayer.

The tree of life is a popular theme also in western art. Famous examples are to be found in masterpieces like Hieronymus Bosch’s (c. 1450 - 1516) The Haywain (1510 - 1516, oil on wood, 147 x 232 cm, El Escorial, Spain) and Lucas Cranach the Elder’s (c. 1472 - 1553) Adam and Eve (1526, oil on panel, 117 x 80.8 cm, Courtauld Institute of Art, London). Austrian symbolist artist Gustav Klimt (1862 - 1918) portrayed his version of the tree of life in his painting, The Tree of Life, Stoclet Frieze (1909, oil on canvas, 195 x 102 cm, Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna). This iconic painting later inspired the external facade of the ‘New Residence Hall’ (also called the ‘Tree House’), a colorful 21-story student residence hall at Massachusetts College of Art and Design, Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.A.

Provenance

CFHILL, Stockholm.

Firestorm Foundation (acquired from the above).

Exhibitions

The Nordic Watercolor Museum, Skärhamn, Sweden, This Garden and its Spirits, 13 October 2024 – 2 February 2025.

Copyright Firestorm Foundation