Josefina Holmlund

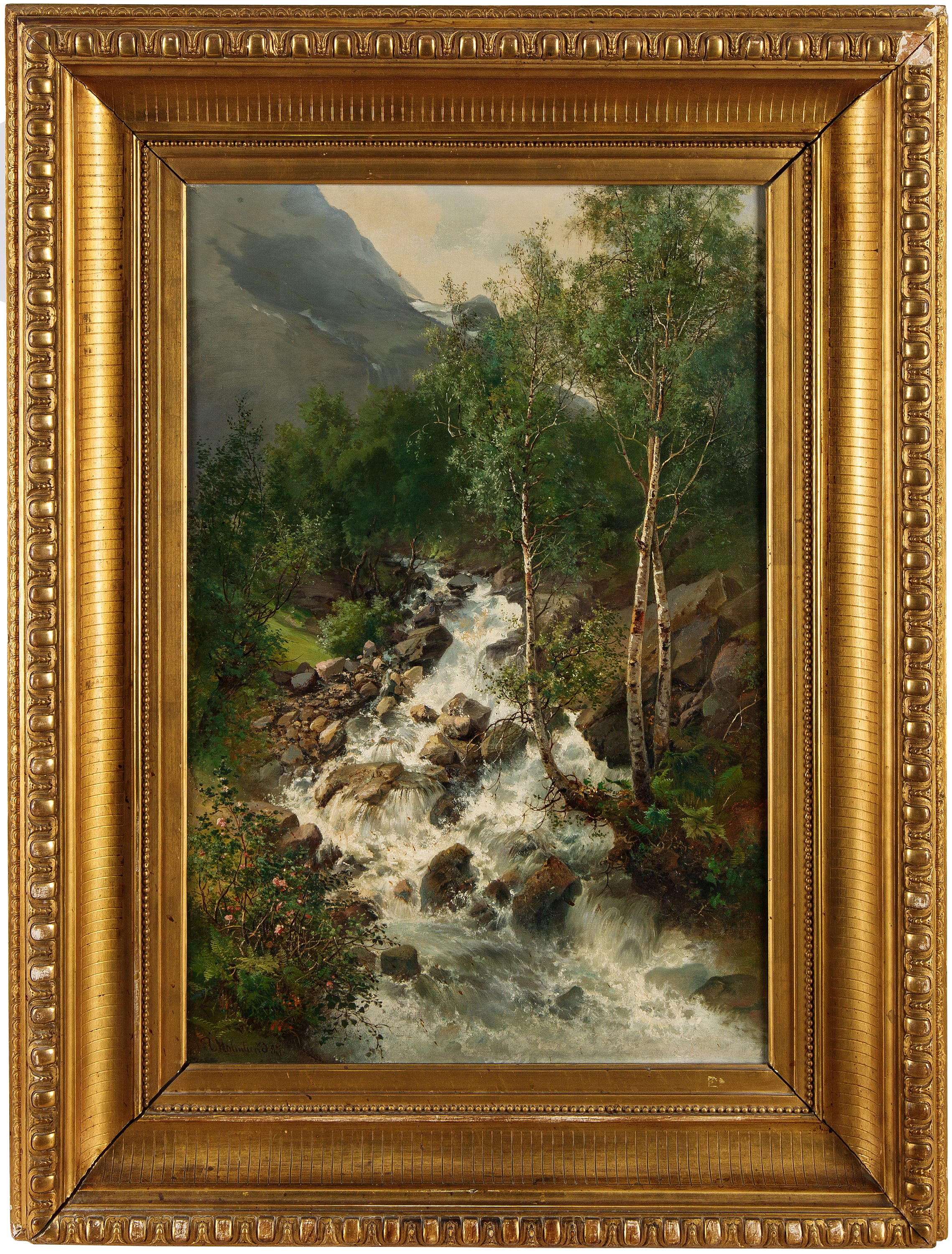

Sommarlandskap med fors (Summer landscape with a rapid)

Signed and dated ‘J. Holmlund 87’.

Norway’s enchanting nature has, for centuries, attracted some of the world’s foremost landscape painters. On the 1st of February 1895, for example, Claude Monet (1840 – 1926) arrived, after having spent five days travelling on railway and ships, the Norwegian capital of Kristiania (Oslo). Monet, who already had a fair knowledge about Norwegian culture through authors like Henrik Ibsen (1828 – 1906) and composers like Edvard Grieg (1843 – 1907), was probably influenced by the late 19th century trend where tourism in Scandinavia attracted travelers from the European continent. Over the next two months, in Sandvika outside of Kristiania, Monet spent long and demanding working days trying to capture the elusive effects of light on the white snow. This Herculean labour resulted in 28 oil paintings, like Mount Kolsås (1895, oil on canvas, 65.4 x 100.5 cm, Sparebanksstiftelsen, The Fine Art Collections, Norway), which were shipped (together with some 30 sketches) back to France afterwards.

Roughly 100 years later, in 2002, David Hockney OM CH RA (born 1937), another artist with a lifelong interest in landscape painting and the rendering of space and light, also arrived in Norway. Constantly drawn to landscape, and in search of new ways of capturing fleeting light and weather conditions, Hockney saw how the muted and rapidly changing atmosphere of northern Scandinavia presented a different challenge that required alternative techniques:

To have longer periods of twilight (when color is not bleached but extremely rich) one has to go north. I made a trip to Norway in May 2002, was very taken with the dramatic landscape and returned to go much further north, when in June the sun never sets at all. You can see the landscape at all hours, 24 hours a day. There is no night. I found myself deeply attracted to it. (David Hockney in G. Evans, Hockney’s Pictures: The Definitive Retrospective, 2004)

Illusionism and flatness appear within these landscape depictions. Often composed out of multiple sheets of paper, capturing different perspectives, Hockney, in compositions like Tufjorden. North Cape (2002, watercolour on [six sheets of] paper, 91.44 x 182.88 cm, private collection), unifies this work with simplified strokes. As in a painting of a postcard or a tourist’s snapshot, the composition and the flat scenery emphasize the lush quality permitted by watercolor, highlighting Hockney’s ability to translate beautifully his own personal experience of nature.

The first people to explore the artistic possibilities that were to be found in the Norwegian landscape, however, were the local artists during, above all, the 19th century. Johan Christian Dahl (1788 – 1857), for instance, was a Danish-Norwegian artist, considered the first great romantic painter in Norway. He is often described as “the father of Norwegian landscape painting” and is regarded as the first Norwegian painter to reach a level of artistic accomplishment comparable to that attained by the greatest European artists of his day. He was also the first to acquire genuine fame and cultural renown abroad, being (alongside his good friend Caspar David Friedrich) named “extraordinary professor” at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts in 1824. As one critic has put it, “J.C. Dahl occupies a central position in Norwegian artistic life of the first half of the 19th century.”

Worth mentioning, amongst the pioneers, is also Dahl’s pupil (from 1843 to 1844) Peder Balke (1804 – 1887), known for portraying the landscape of Norway in a romantic and dramatic manner. During the summer of 1830 he walked from Rjukan (where Josefina Holmlund would paint some six decades later) in the Vestfjorden valley, through Telemark County, all the way to the city of Bergen, and then back to Rjukan through Vossevangen to Gudvangen, further over Filefjell to Valdres and then across the mountains to Hallingdal. Along the way, he painted and drew small sketches that were later developed into paintings.

The personal union of the separate kingdoms of Sweden and Norway under a common monarch (and common foreign policy that lasted from 1814 until its peaceful dissolution in 1905) meant that a handful of Swedish artist’s also dedicated time to landscape painting in Norway in the 19th century. Famous examples could be found in Prince Eugen of Sweden and Norway, Duke of Närke (1865 – 1947). Prince Eugen was a great admirer of Norwegian nature and frequently visited Kristiania. His letters show that he preferred its artistic milieu to the more constrained Stockholm one. His most notable Norwegian friends were the painters Gerhard Munthe (1849 – 1929) and Erik Werenskiold (1855 – 1938); he remained attached to them and to Norway until his death. Prince Eugen was also the only Swede represented at an exhibition in Oslo in 1904. The explanation being that he was a prince of Norway until 1905 and that his relations with the Norwegian artists caused him to be seen as Norwegian until the dissolution of the union. Prince Eugen spent the summers of 1889 and 1890 painting in Valdres, Norway, from where he wrote (in a letter to his friend Helena Nyblom): “I think the vigorous colorful nature here is healthy for me”.

Prince Eugen’s friend Ernst Josephson (1851 – 1906) had explored the Norwegian landscape as early as in the 1870s. In the summer of 1872, he left Kristiania and travelled, by steamship and train, to Åmot, from where he walked 70 miles to Eggedal. The beautiful valley offered magnificent views:

Never have I seen anything comparable. [...] At the most I have only sensed something similar in the music of Beethoven. So enormous! And sunlight playing, with beguiling beauty, down in the valleys while melancholy shadows of clouds slowly glide over the mountain masses. One feel liberated from, and left outside of, this whole miserable world, so close to eternity! It’s a moment of immaculate life.

Josephson would return to the magnificent landscape vistas of Norway. Some of his plein air paintings from the trip, like Bäck i skogen. Eggedal / Stream in the forest, Eggedal (1884, oil on wood, 64 x 52 cm, Sven-Harrys konstmuseum, Stockholm), would lay the foundation for Josephson’s ultimate masterpiece Strömkarlen (1884, oil on canvas, 216 x 150 cm, Prins Eugens Waldemarsudde, Stockholm), executed later that year and nowadays on permanent display in Prince Eugen’s palatial art nouveau villa in Stockholm.

Some of his letters from the summer of 1884 talks about: “The solitude and the singing waterfalls, the muffled wailing of the rushing rapids, the hanging branches of the fir trees and the youthful growth of the birches; ferns, lush moss and fantastic stones” (to his friend Carl Wahlund, July 29) and “High mountains, gentle lines, endless forests, rapids and mossy rocks, flowering rosehip bushes, birches, ferns and spruces. [...] How beautiful this is!” (to fellow painter Axel Borg, undated).

Josephson’s lyrical words could equally well be used to describe Holmlund’s Sommarlandskap med fors (Summer landscape with a rapid), painted a mere three years later in 1887. Well-travelled, Holmlund, besides studying in Düsseldorf, visited Italy, France and Finland. Norway, which held a special place in her heart, was visited in 1870 and 1877. Her style was initially influenced by the traditional academic approach of the Düsseldorf School but when French-inspired outdoor painting came along in the 1870s, these features became less apparent, even though they never completely disappeared. Her later works, to which Sommarlandskap med fors (Summer landscape with a rapid) belongs, thus gives way to a freer plein-air rendering of the Nordic landscape.

Surprisingly little biographical information about Holmlund has been preserved. One of the best descriptions were provided, as early as 1897, by Hjalmar Cassel, who wrote (in IDUN, N:o 8, Friday 26 February 1897):

Influenced by more modern trends in art, Josefina Holmlund has in recent years moved away from the ideas of the Düsseldorf school, even though one can still trace lingering influences in her paintings. Particularly meticulous in her preparatory drawing, and sensitive to the correct use of perspective, she devotes unusual care to her paintings. She would never allow for a hastily assembled, unfinished, sketch to leave her studio. But one mustn’t therefore think that she, like many of the artists of an older generation, works unnecessarily pedantically. On the contrary, she paints extremely quickly and, thanks to a highly developed technique, is able to produce a very respectable volume of work annually, even now in her old age. Few artists, even the most youthful, work as persistently as she does – in the summer out in the open, in the winter in the studio. Thanks to a quick, youthful temperament and a rather unusual vigor for her age, she has still been able to continue her beloved study trips, which for the true landscape painter constitute the very intercourse with nature, from which the artist’s inspiration seeks its nourishment. Miss Holmlund’s study trips have mainly taken place in Scandinavia. Her art is Nordic, and she has drawn motifs from the Nordic countries for almost all her paintings. What she loves in nature is the grandeur and picturesqueness. She has painted Norway’s fjords and mountains with fondness, and in the roaring waterfalls of the grandiose Norwegian mountain landscapes as well as in the mountainous regions of our own country, she has found grateful subjects for her brush. […] If Josefina Holmlund is not modern in the sense that she has quickly followed today’s fashion in painting, she should nevertheless, despite her seventy years of age, be counted among the young, because the artistic enthusiasm is still so alive in her and because her desire to learn is stronger than ever.

Provenance

Bukowskis, Stockholm, Sale E818, Selected Classics Online – 19th and early 20th century paintings, 27 November 2021, lot 1350307.

Firestorm Foundation (acquired at the above).

Copyright Firestorm Foundation