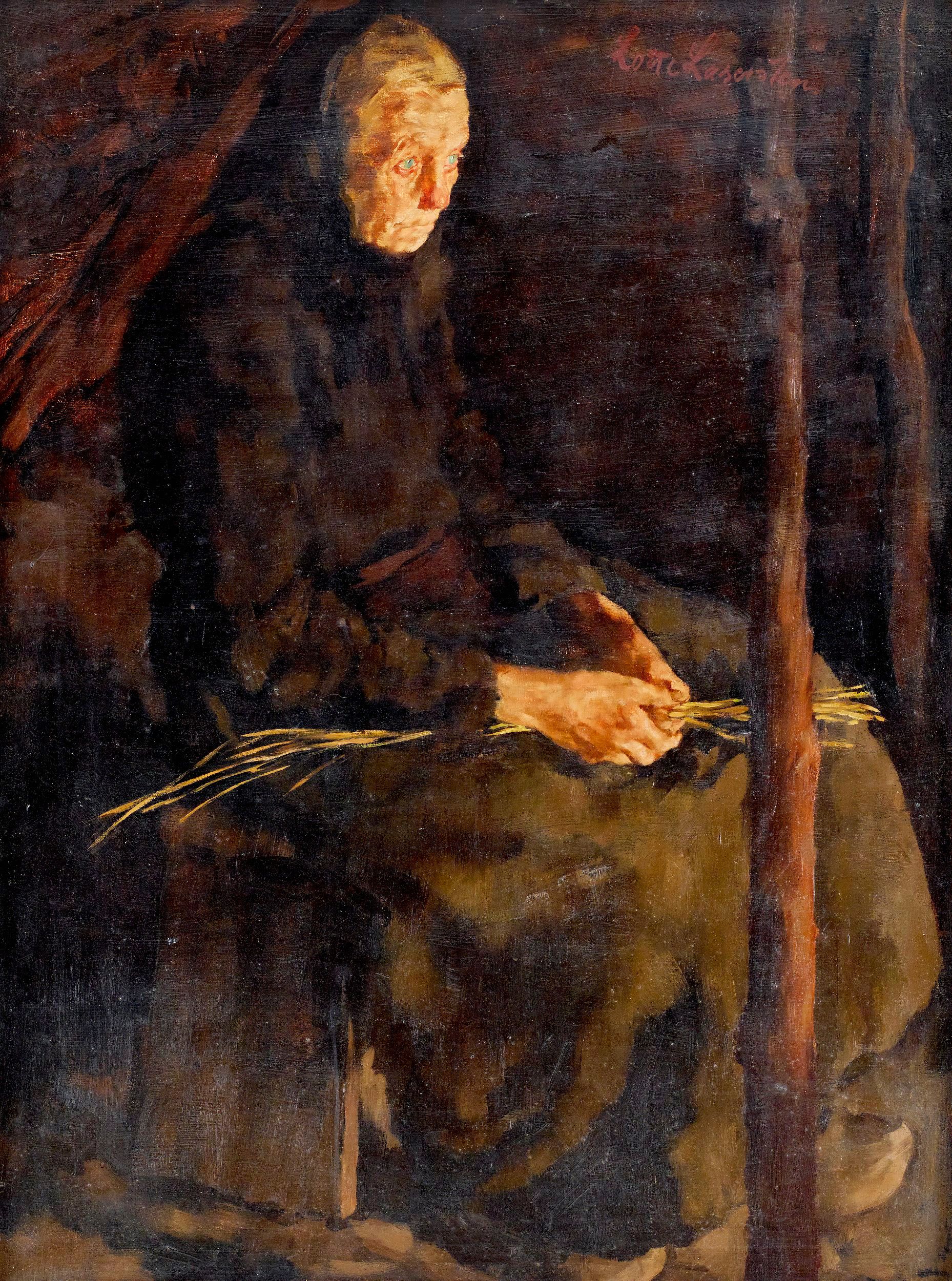

Lotte Laserstein

Sitzende Alte

Signed Lotte Laserstein

Sitzende Alte was executed, at the height of Lotte Laserstein’s powers, in 1932 (a mere year before her “brilliant rise”, that the German art critics predicted and attributed to her in the 1920s, came to an abrupt halt, when the Nazis came to power in 1933). By this time Laserstein had completed some of her most venerated masterpieces, like In meinem Atelier / In My Studio (1928, oil on panel, 46 x 73 cm, private collection, USA) and Abend über Potsdam / Evening over Potsdam (1930, oil on panel, 110 x 205 cm, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie).

When Laserstein painted these works, in the late 1920s and early 1930s, German women had gained independence and were increasingly able to assert themselves in workplaces and public life (often adopting a slightly more masculine look, sporting fashionable Herrenschnitt or Bubikopf haircuts, and smoking cigarettes etc.). Laserstein, as a successful professional single woman, embodied this new ideal herself and her, slightly androgynous, look at the time was immortalized in many of her self-portraits, for example, Selbstportrait mit Katze /Self-portrait with a Cat (1928, oil on plywood, 61 x 51 cm, Leicester Museum and Art Gallery, United Kingdom).

Laserstein’s portrayal of the Neue Frau (“New Woman”) type of the German Weimar Republic era (9 November 1918 – 23 March 1933) came to define much of her production in works like Russiches Mädchen mit Puderdose / Russian Girl with Compact (1928 oil on panel, 32 x 41 cm, Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main, Germany) and Polly Tieck (1929, oil on canvas, 90 x 80 cm, private collection, Sweden). Many of these works, thematically as well as stylistically, trace their lineage back to the legendary Im Gasthaus / In the Tavern (1927, oil on wood, 54 x 46 cm, private collection, Germany), a triumphant painting for a female artist of the time, that was acquired by the City of Berlin in 1928 and later disappeared before resurfacing again, under the title Sitzende Frau mit schwarzem Hut und Handschuhen in einer Bar, in a minor auction in Munich (Hugo Ruef, Alte und Moderne Kunst, 28 June) in the summer of 2012 (with a realized hammer price of Euro 110,000 compared to the estimate of Euro 900….). The painting (Laserstein’s first publicly exhibited work in Berlin, that was well received at the Prussian Academy’s Spring exhibition in 1928), depicting a solitary urban female in a bar, or a café, can easily be regarded as a popular avant-garde trope of Weimar representation. Representing the new woman of the 1920s she sits by herself (without a man to accompany her…), is left to her own devices, and has indifference written all over her facial expression and body language.

In this sense, she is a typical “New Woman”, or Neue Frau of the 1920s. In the Weimar era, many women were financially independent for the first time. According to the stereotype of the Neue Frau, these emancipated women looked to find more, and different, kinds of excitement in their lives, rather than falling into the monotonous traps of wifely duties and family life. And yet, this search for stimulation could lead to blasé attitudes. There was a certain freedom afforded to these new women, but the luxury of freedom was often, eventually, accompanied by boredom, relating to a reluctance to participate in an increasingly oppressive society (the Nazi regime of the 1930s). While these women were trying to carve out a new path in Berlin, the struggle to achieve these goals often proved difficult and slow, which could manifest itself in frustration, as represented in Laserstein’s painting of a bored and blasé modern woman in a metropolitan café.

There’s nothing bored and blasé, however, about the ageing woman in Sitzende Alte. On the contrary she could be viewed as a rural and rustic mirror image of the sophisticated, but emotionally empty, Neue Frauen that Laserstein mixed with in the bustling streets and crowded cafés of the Weimar era Berlin. The countryside of rural Germany actually played an important (if however often neglected) part in Laserstein’s production. In the 1930s (before the Nazis put an end to it in 1935, when they shut her studio down) she took her own private art students on annual excursions to the countryside, and 1932 was no exception. Anna-Carole Krausse writes (in [Ed.] Iris Müller-Westermann & Anna-Carola Krausse, Lotte Laserstein. A Divided Life, exhibition catalogue, Moderna Museet, Malmö & Stockholm, 2023):

From the early 1930s there are signs not only of a stylistic shift in Laserstein’s work, but of a broader thematic range: the brushwork is looser, the meticulous detail moves backstage, and new motifs appear. While the modern urbanite had previously been her focus, she now also began painting peasants, day labourers, landscapes, and animals. This surprising interest in rural subjects that had previously played no part in the artist’s output is by no means an indication that she was turning to the conservative ideas that set the tone from 1933 onwards. The explanation lies elsewhere: in 1931 she began undertaking lengthy excursions to the countryside with her students. […] In 1932 they went to Neu St. Jürgen, a little village on the bog Teufelsmoor, near Bremen, not far from the former artists’ colony Worpswede, where Paula Modersohn-Becker had lived. The painters from Berlin stayed in a simple guesthouse and hired children, elderly people in need of extra income, and day labourers to come and sit for them in return for a decent payment.

The aging woman depicted in Sitzende Alte probably belongs to this group of “elderly people in need of extra income” from the summer excursion of 1932. Similar compositions (and formats/sizes) can be found in other works from this group, like Alte Frau mit vier Kindern / Old Woman with four Children (1932, oil on wood, 100 x 75 cm, private collection, Germany, M 1932/16) and Warten / Waiting (1932, oil on canvas, 90 x 73 cm, private collection, Sweden, M 1932/18).

The overall dark palette of Sitzende Alte draws our attention to the blue colour of the old woman’s eyes. The intense, but slightly introverted, gaze (resting on the open fire but directed towards some far-off world), also, connects her to another celebrated painting by Laserstein: Meine Großmutter / My Grandmother (c. 1924, oil on canvas, 47.5 x 34.5 cm, Cartin collection, New York, USA), depicting Ida Birnbaum.

The painterly depiction of rustic farmers and rural characters can be traced back hundreds of years. One early example could, for instance, be found in Albrecht Dürer’s (1471 – 1528) engraving Drei Bauern im Gespräch / Three Peasants in Conversation (c. 1497). Flemish painter Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c. 1525 – 1569) is best known for his busy tableaus of 16th century Netherlandish peasants that range from the banal to the absurd in celebrated paintings like The Peasant Wedding (1567, oil on panel, 114 x 164 cm, Kunsthistoriches Museum, Vienna) and its pendant (?) The Peasant Dance (1567, oil on panel, 114 x 164 cm, Kunsthistoriches Museum, Vienna).

In the 17th century, peasants figure primarily in ‘genre pieces’ (scenes from daily life), in which they appear as simple folk in everyday settings, either at work or drinking in a tavern. Peasants occur frequently in paintings and prints by Rembrandt van Rijn (1606 – 1669), Adriaen van Ostade (1610 – 1685) and Cornelis Pietersz. Bega (1631/32 – 1664), among others. Peasant life was taken much more seriously in the 19th century by painters of the Barbizon School, including Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796 – 1875), Jean-François Millet (1814 - 1875) and Charles-Francois Daubigny (1817 – 1878). Showing respect for their humble yet important labour, they depicted peasants at work or praying at the edge of a field.

Through scenes like Sitzende Alte, and other works from the painting excursions of the summers of the early 1930s, Laserstein connects to this time-honored tradition in Western art.

According to the inscription verso, Sitzende Alte comes with an interesting provenance (of the more peculiar kind): “Erik Lindgren, Borgvattnet”, which deserves to be somewhat clarified. The old vicarage in the Jämtland village of Borgvattnet (c. 100 kilometers east of Östersund, in the north of Sweden) has long been referred to as one of the world’s most haunted houses. The wooden vicarage was built in 1876, and the first priest moved in the same year. It was in 1927, however, that the first known “haunting”, or paranormal activity, occurred at the vicarage, when the priest Nils Hedlund witnessed how the laundry inexplicably was being torn off the washing line. After that, several similar things happened over the years, but it wasn’t until 1947 that the phenomenon of the haunted vicarage became public knowledge. The resident of the vicarage at that time, chaplain Erik Lindgren, then relayed his experiences to a journalist, whose article eventually were picked up by national press in Sweden.

When Lindgren had arrived at the vicarage in 1945, he, already on the first evening, heard sounds of heavy objects being dragged across the floor. The only problem was that his household goods had not yet arrived, and the upstairs rooms were completely devoid of furniture. On another occasion, he was reading in his rocking chair when he was suddenly thrown out of it by unknown forces and landed on the floor. Having, somewhat perplexed, returned to the rocking chair he was, once again, thrown to the floor!

Lindgren was the last priest to live in the vicarage. He only put up with the hauntings for two years before he moved out and got a new home in 1948. Local entrepreneur and merchant Erik Brännholm (1911 – 1996), bought the vicarage in 1970 and converted it into a hotel. Over the years, Borgvattnet’s vicarage has been referred to as one of the world’s most haunted houses and those who manage to stay over (several guests have been known to flee in the middle of the night) receive a coveted diploma in the form of an overnight certificate.

Provenance

Chaplain Erik Lindgren, Borgvattnet, Sweden.

Stockholms Auktionsverk, Stockholm, Modern Art & Design, 21 October 2015, lot 418 (under the title Gammal gumma).

Uppsala Auktionskammare, Uppsala, Sweden, Modern konst, 16 June 2016, lot 886.

Private collection, Sweden.

Firestorm Foundation (acquired from the above).

Literature

Anna-Carola Krausse, Lotte Laserstein (1898 – 1993). Leben und Werk, 2006, catalogued and illustrated, in accompanying CD (“Werkverzeichnis”), under M 1932/17.

Copyright Firestorm Foundation