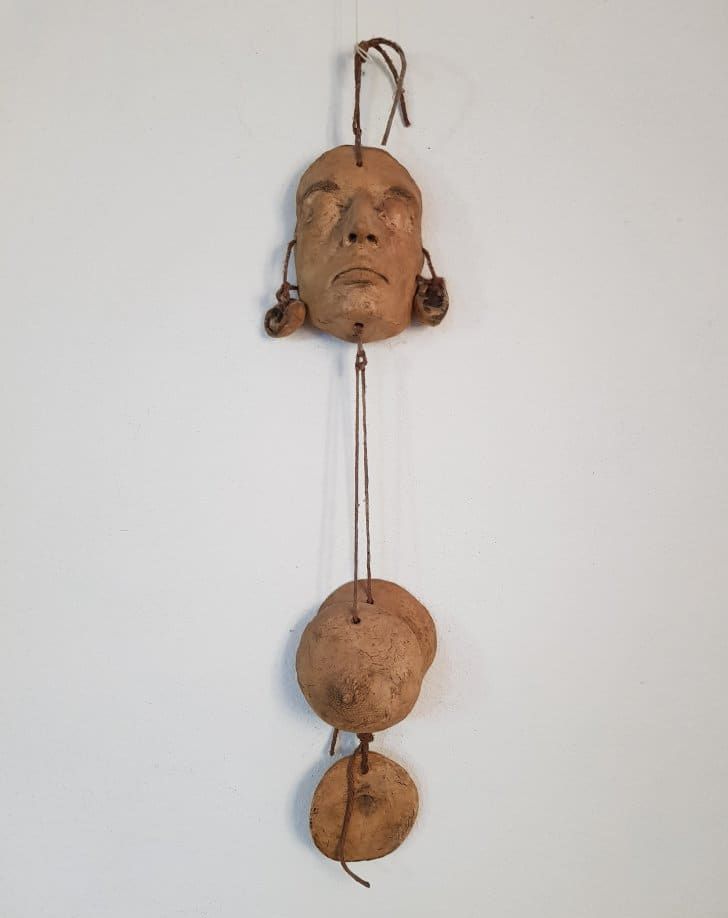

Marisol Escobar

Self portrait

Marisol Escobar held a unique position within the New York City art scene in the 1960s and 1970s. Albert Boime writes (in ‘The Postwar Redefinition of Self. Marisol’s Yearbook Illustrations for the Class of ‘49’, American Art, Vol. 7, No. 2, Spring 1993):

One of the least understood pioneers of Pop Art has also been the lone female survivor of the movement, Marisol. Her ingenious tableaux assemblages that combine direct carving, painting, drawing, photographs, and found objects have consistently defied neat categorization. While not borrowing images directly from popular media, she nevertheless endows celebrities (including herself) and groups of ordinary types with the Pop Art look by whimsically presenting their physical presence and characteristic fashions in three-dimensional assemblages.

As a girl growing up in Caracas, Venezuela (in the 1930s and 1940s), Marisol had enjoyed reading Spanish translations of popular American comic books. Dick Tracy, Popeye and Donald Duck belonged to her favourites. This childhood passion was shared by a young boy (and future friend of Marisol’s) growing up in a poor part of Pittsburgh: Andy Warhol (1928 – 1987), who later in life would return to these themes in iconic early Pop art works like Dick Tracy and Popeye. However, as pointed out by Albert Boime:

Marisol’s work is rarely identified with cartooning because she works in three dimensions, yet she uses her medium graphically by often painting or drawing outlines of limbs on her blocky bodies and rendering heads on one or more sides of a cube – a hallmark of her style. In this sense, her work comes closer to the tradition of caricature than cartoons. Whereas Lichtenstein and Warhol cautiously inflected the comic images they appropriated from the mass media, Marisol constructs her figures with elements of irony and acerbic wit that comment on their distinctive physical and personality traits.

Marisol’s Self-portrait from 1974 is a good example of her highly personalized style. During the Postwar period, there was a return of traditional values that reinstated social roles, conforming race and gender within the public sphere. According to Holly Williams, Marisol’s sculptural works instead toyed with the prescribed social roles and restraints faced by women during this period through her depiction of the complexities of femininity as a perceived truth. Marisol’s practice demonstrated a dynamic combination of folk art, dada, and surrealism – ultimately illustrating a keen psychological insight on contemporary life.

By displaying the essential aspects of femininity within an assemblage of makeshift construction, Marisol was able to comment on the social construct of “woman” as an unstable entity. Using an assemblage of plaster casts, wooden blocks, woodcarving, drawings, photography, paint, and pieces of contemporary clothing, Marisol effectively recognized their physical discontinuities. Through a crude combination of materials, Marisol symbolized the artist’s denial of any consistent existence of “essential” femininity. “Femininity” being defined as a fabricated identity made through representational parts. An identity which was most commonly determined by the male onlooker, as either mother, seductress, or partner.

Using a feminist technique, Marisol disrupted the patriarchal values of society through forms of mimicry. She imitated and exaggerated the behaviours of the popular public. Through a parody of women, fashion, and television, she attempted to ignite social change. The sculptural practice of Marisol simultaneously distanced herself from her subject, while also reintroducing the artist’s presence through a range of self-portraiture found in every sculpture. Unlike the majority of Pop artists, Marisol included her own presence within the critique she produced. She used her body as a reference for a range of drawings, paintings, photographs, and casts. This strategy was employed as a self-critique, but also identified herself clearly as a woman who faced prejudices within the current circumstances.

Provenance

Sidney Janis Gallery, New York.

Private collection, Sweden (acquired from the above).

Firestorm (acquired from the above).

Copyright Firestorm Foundation