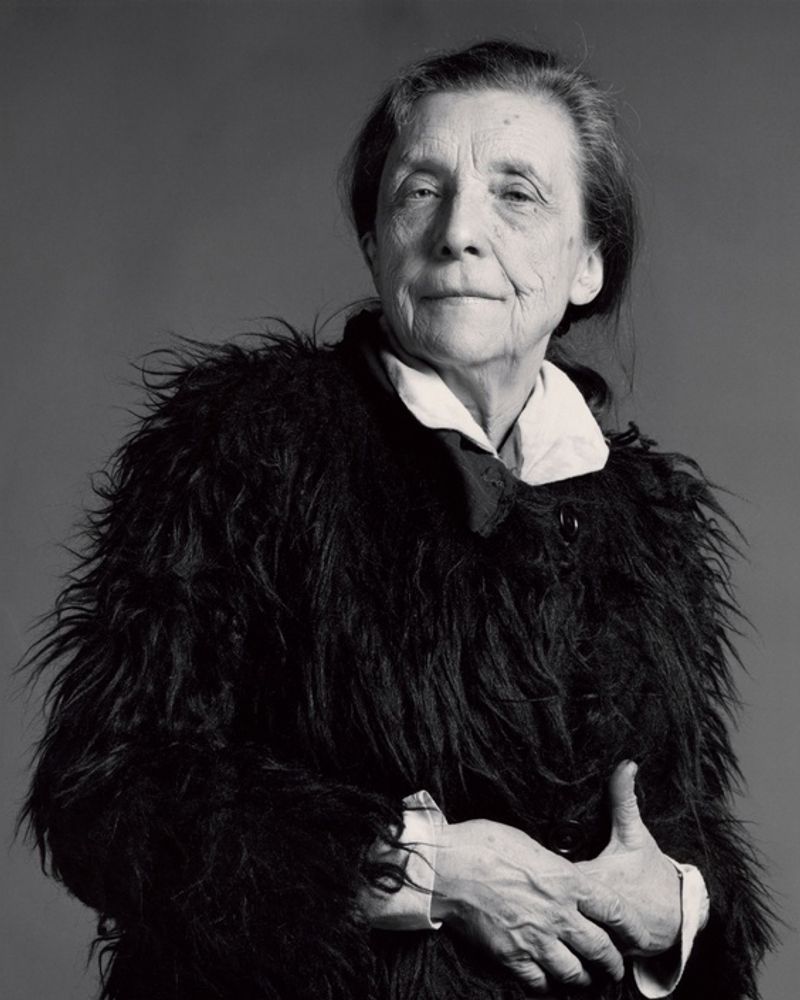

Louise Bourgeois

French American artist Louise Bourgeois was one of the greatest artists of the 20th century. It is therefore a bit surprising that when the Royal Academy of Arts in London staged its comprehensive survey of American art in the 20th century (1993), the organizers did not consider Bourgeois’ work of significant importance to include in the survey! This was, however, rectified seven years later when her works were selected to be shown at the opening of Tate Modern in London.

Although best known for her large-scale sculptures and installation art, she was also a prolific painter and printmaker (Bourgeois’ printmaking flourished during the early and late phases of her career: in the 1930s and 1940s, when she first came to New York from Paris, and then again starting in the 1980s, when her work began to receive wide recognition. Over the course of her life, Bourgeois created approximately 1,500 printed compositions. In 1990, Bourgeois decided to donate the complete archive of her printed work to the Museum of Modern Art, New York). In the later stages of her career, Bourgeois continued her exploration of the use of less traditional materials, such as stuffed fabric, for her sculptures, thus challenging the accepted elevation of hard-wearing materials such as bronze or stone.

Bourgeois’ work is powered by confessions, self-portraits, memories, fantasies of a restless being who is seeking through her sculpture a peace and an order which were missing throughout her childhood (Bourgeois repeatedly returned to the memories of an unhappy childhood where her father betrayed her ailing and sickly mother with a variety of different women and mistresses, including Bourgeois’ English governess). She felt she could get in touch with issues of female identity, the body, and the fractured family long before the art world and society at large considered them as subjects to be expressed in art.

Bourgeois has explored the concept of femininity through challenging the patriarchal standards and making artwork about motherhood rather than showing women as mere muses or ideals. She has been described as the “reluctant hero of feminist art”. Bourgeois had a feminist approach to her work like fellow artists such as Agnes Martin (1912 - 2004), less driven by the political but rather made work that drew on their experiences of gender and sexuality, naturally engaging with women’s issues. Motherhood is another recurrent theme (Bourgeois considered her mother to be intellectual and methodical, and the continued motif of the spider in her work often represents her mother).

Bourgeois graduated from the prestigious Sorbonne in 1935. She then began to study art in Paris, first at the École des Beaux-Arts and École du Louvre, and after 1932 in the independent academies of Montparnasse and Montmartre such as Académie Colarossi, Académie Julian and Académie de la Grande Chaumière. From 1934 to 1938, she is said to have apprenticed herself to some of the so-called “masters” of the time, including Fernand Léger (1881 – 1955), Paul Colin (1892 – 1985), and André Lhote (1885 – 1962). Later, however, Bourgeois became disillusioned with the conception of patriarchal genius which dominated the art world, a change motivated in part by the refusal of “male geniuses” to recognize women artists.

Having set up her own gallery in 1938, showing works by Eugène Delacroix (1798 – 1863) and Henri Matisse (1869 – 1954), she one day came across the visiting American art professor Robert Goldwater as a customer. Soon after they married and moved across the Atlantic to New York City, where they settled in 1938. For Bourgeois, the early 1940s represented the difficulties of a transition to a new country and the struggle to enter the exhibition world of New York City. In 1945, however, she was included in an exhibition, called The Women, of fourteen women artists at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century. While this exhibition stimulated debate about the place of women artists in the art world, it also defined them as separate from their canonized male counterparts and reinforced the damaging notion of a universally feminine experience. Commenting on her reception as a woman artist in the 1940s, Bourgeois said that she didn’t “know what art made by a woman is. There is no feminine experience in art, at least not in my case, because not just by being a woman does one have a different experience.” Even though she rejected the idea that her art was feminist, Bourgeois’ subject was the feminine. In the late 1960s, her imagery became more explicitly sexual as she explored the relationship between men and women and the emotional impact of her troubled childhood. With the rise of feminism, her work found a wider audience.

In 1973, Bourgeois started teaching at the Pratt Institute, Cooper Union, Brooklyn College and the New York Studio School of Drawing, Painting & Sculpture. From 1974 until 1977, she worked at the School of Visual Arts in New York where she taught printmaking and sculpture. She also taught for many years in the public schools in Great Neck, Long Island. In 1978 Bourgeois was commissioned by the General Services Administration to create Facets of the Sun, her first public sculpture. The work was installed outside of a federal building in Manchester, New Hampshire.

With the advent of the 1980s recognition finally materialized for Bourgeois. At the age of 70, Bourgeois received her first retrospective in 1982, by the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. Until then, she had been a peripheral figure in art whose work was more admired than acclaimed. The New York Times said at the time that that “her work is charged with tenderness and violence, acceptance and defiance, ambivalence and conviction”. Bourgeois had another retrospective in 1989 at Documenta 9 in Kassel, Germany.

Between the years of 1984 and 1986, Bourgeois created a series of sculptures all under the title Nature Study which continued her lifetime commitment of challenging patriarchal standards and traditional methods of femininity in art. In 2010, the last year of her life, Bourgeois used her art to speak up for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) equality. She created the piece I Do, depicting two flowers growing from one stem, to benefit the nonprofit organization Freedom to Marry. Bourgeois has said “Everyone should have the right to marry. To make a commitment to love someone forever is a beautiful thing.” Bourgeois had a history of activism on behalf of LGBT equality, having created artwork for the AIDS activist organization ACT UP in 1993.

Bourgeois died of heart failure on 31 May 2010, at the Beth Israel Medical Center in Manhattan, New York. She had continued to create artwork until her death, her last pieces being finished the week before.

Copyright Firestorm Foundation